By Brian Susbielles

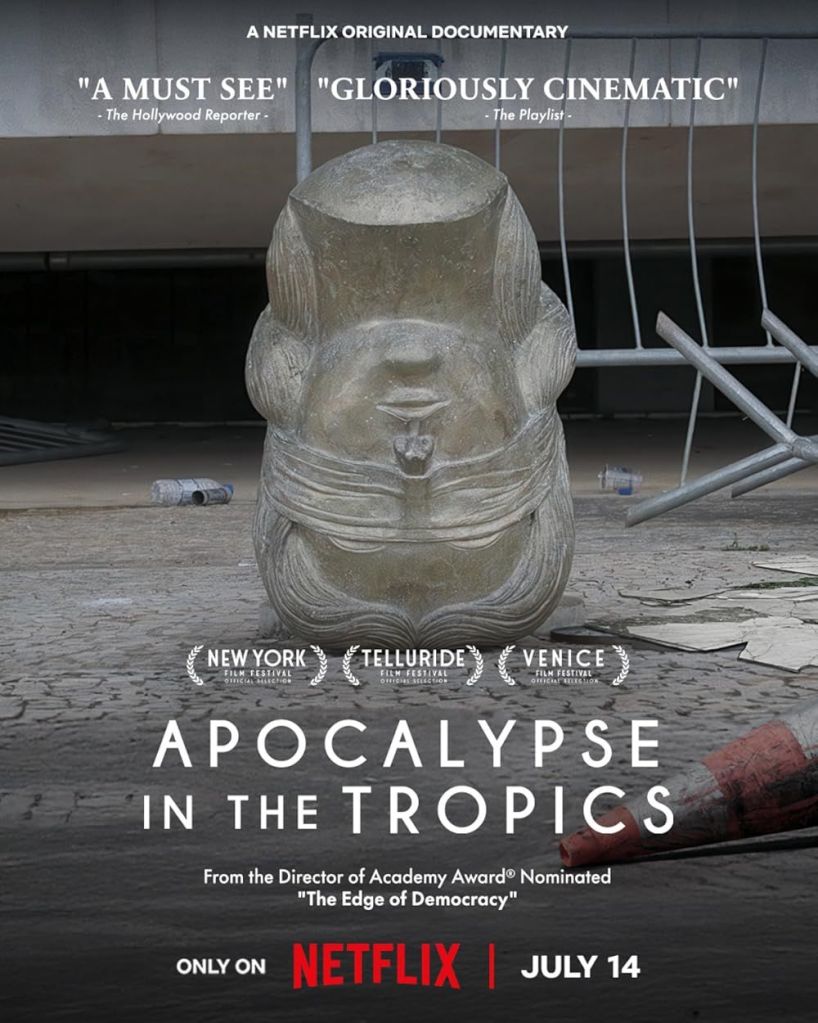

I think the last thing anyone wants to hear or read about is the rise of far-right populist leaders like the one residing at 1600 Penn in D.C. But when you have a parallel government down in South America with an even scarier ideology and a country’s background that has a history of instability, it makes you take a sigh of relief that there’s a little more hope in the United States than in places with a knack for coups. Director Pedra Costa’s previous film, The Edge of Democracy, played out the events leading up to her new film, Apocalypse In The Tropics, and how much Brazil’s faith in democracy tethered on the brink of collapse thanks to wide-range exposure of corruption top to bottom. One of the film’s minor characters, a Senator named Jair Bolsanero, would surf on the country’s anger to win the Presidency in 2018 thanks to the help of a rising movement, the Evangelical community.

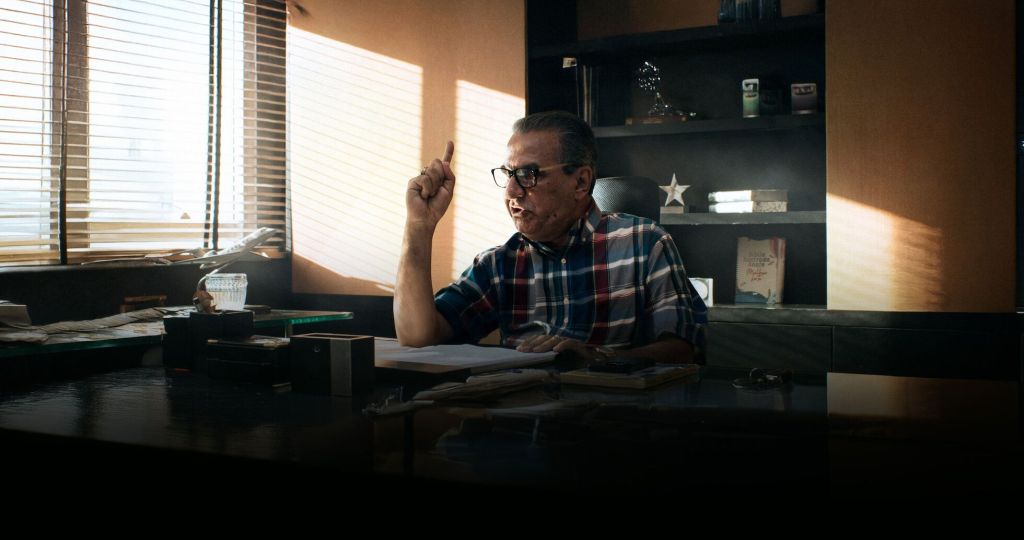

In multiple chapters, Costa introduces us more in Bolsanero’s inner circle, with the main figure being noted televangelist Silus Malafaia. Malafaia, a millionaire with a media empire reminiscent of American figures like Billy Graham (whose archive footage of him is part of the film’s narrative), is a charismatic figure who bluntly tells people that all of these secular things like LGBTQ issues and abortion are from the Devil in the from of the ruling socialist Workers’ Party. Its charismatic leader, former President Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva, is arrested for corruption, and opens the door for Bolsanero’s election and the power of the Evangelical movement to intercede with politics for a Christian nationalist state, going against Brazil’s laws supporting separation of church and state.

Following the next four years of Bolsanero’s term, Costa’s narration captures on the ground the growing force of the Evangelical movement whose policies are based on the Bible and not on reality. During the COVID epidemic, Brazil had the second highest number of deaths, over 700,000, as Bolosnaro simply regards the issue as people just dying like we will all do and the Evangelicals that backed up only said praying to God will stop the disease. Meanwhile, people are begging for oxygen tanks as hospitals have overflowed. Under Malafaia’s influence, an Evangelical Supreme Court judge is nominated, and even with a Senate led by the opposition, the massive pressure leads to the nominee’s confirmation.

Meanwhile, “Lula,” as he’s affectionately called, has his charges of corruption dropped on his appeal, and he becomes the immediate threat to Bolsanero’s re-election chances. It’s in the year prior to the election in November 2022 that it turns into a holy war, as one chapter is titled, where Bolsanero’s side talks about being ordained by God and Lula warns about the threat of a dictatorship coming back. Echoes of the military dictatorship that overthrew Brazil’s democracy in 1964 and the “ghosts of communism” are referenced, especially when the United States aided in that coup and funded countermeasures to stop Catholic priests talking about the injustices in the country. Even in the 2020s, sixty years after the military dictatorship began, those lingering Cold War battles are still around.

When watching the movie, those who have no idea of Brazil’s politics – I do as someone with knowledge of some of the international politics – will realize the mirror to current American politics. It’s bone chilling to think copycat events and comments were happening, all to undermine democracy and to install an uprising with the expectation that Christian nationalism with military assistance could come back. Their source is Biblical teachings from many Evangelical influencers besides Malafaia have spoken of and the literal view of the Book of Revelation. Costa, who also narrates the movie as she did in Edge of Democracy, details the influences and seeds of thought that has carried the country to this point in time, even in 2025 after the time of this documentary takes place.

Apocalypse In The Tropics is the real story of what happens when a singular force under false pretenses tries to take over a country through democratic and undemocratic means. Pedra Costa shows in real-time the dramatic shift of moods and the religious furor that reaches dangerous levels and one that can be spotted all over the world. Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here is a story that has happened in Brazil and other Latin American countries multiple times in the last 100 years, and seeing it regurgitate is a sickening feeling The apocalypse within the modernity of Brazil’s capital of Brasilia is a forewarning that not even a modern world can contain the energy of Biblical-style forces.

4 ½ stars

Follow me on X: @brian_cine (Cine-A-Man)

Leave a comment